By reading this article you will understand:

- What we mean when we reference the attention economy.

- Why engagement with content is best measured by demand.

- Why the attention economy now dictates that we must use new ways to measure engagement on a global scale.

“Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii” by Nam June Paik (1995): 15 x 40 x 4 ft., at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photo credit: centralasian/flickr.com

Over the next 12 months a few new players, and in some ways not-so-new at all, will be entering and beginning to crowd the subscription-video-on-demand (SVOD) space. As each player hopes to be a winner, increasing their share of consumers’ time and attention, a new era is dawning. Revolutionary changes to the business of television are expected, the era of the “Streaming Wars” is truly upon us.

Meanwhile, audiences are fearful that the content ecosystem is not only getting more crowded, but also more fragmented, dispersed, and expensive. Still, audiences, content creators and distributors can agree upon at least these two truths: 1) consumer attention is finite and 2) good characters and good storytelling are invaluable.

In “The 30,000 Foot View: A Preview of the 2020 Streaming Wars”, Parrot Analytics provides a unique industry perspective. We will highlight the opportunities for each of these players to keep the content ecosystem accessible, exciting, and entertaining for audiences – because we all love to experience the magic of content.

The attention economy

In their Harvard Business Review article, Mark Purdy and Gene Reznik argue that going forward, every company, including even those not currently involved in entertainment, must think and act like an entertainer. It is not enough to simply be a producer or seller of goods – instead, in an age that is defined by interactive and immersive experiences, companies must reinvent themselves to stand out in the crowd of choices and options.

What about the entertainment business itself? Many have argued that the future of media consumption is one of convergence driven by interactivity.

Users not consumers: The convergence towards interactivity

Netflix is one of many companies that are now serving up content across multiple platforms and audience universes. As a leader of the disrupters and streamers, Netflix has begun transforming their viewers to partners in storytelling. Take Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, for example, or Bear Grylls’ You vs. Wild – two recent titles that allow audiences to navigate their own path through the story with the help of a TV remote.

Netflix has also ventured into other interactive formats such as Fortnite with cross-over promotional strategies. In this 250 million strong gaming universe the streamer has a single-minded purpose: To grab attention, to convert this into an emotional investment or at least some form of curiosity and then to extract maximum commercial value.

Through these interactive forms of storytelling, audiences are invited to play a role in elevating their experiences and to become fully immersed in content. The trend here is clear. Netflix is only a symptom of an attention economy in which the demand for content is not sustainable if audiences remain consumers or viewers. Passive viewers are less invested and are happier to not re-subscribe for a service.

SVODs everywhere are desiring interactive users. New streamers such as Quibi and Facebook Watch appear to be geared towards capitalizing on interactive tactics — take for example the Spielberg horror series that will only be available for watching at night or Skam on Facebook Watch, which inspired consumers to engage interactively on real-world social media accounts.

D. T. Max of the New Yorker argues that this “engagement” will drive the industry. Specifically, he states, “advertisers want to pay for how often you like, post, and click, rather than for how long you passively watch.” In other words, stories are designed to create fandoms. Today’s stories do more than fill time with entertainment. They aim to become embedded into the social, emotional, and intellectual lives of audiences, often not without controversy.

Yet, increasing convergence also means blurred lines between classical content categories. At Parrot Analytics we have been quantifying this trend for a while now, and in the process becoming the global leader in measuring and capturing what all content producers want: Attention, driven by consumer activity.

Attention is not only viewership, it is not only ratings of quality — after all, interactive mediums have never used these as standards. Rather, it is something much more all-encompassing: True audience attention happens when fans are demanding content passionately and this involves interaction, connection, and sharing. Consumers, when fully engaged, express their demand for a TV series in a plethora of different ways across multiple channels and devices. Thus, it is important to measure global audience demand holistically.

In the attention economy, demand is finite

Though the volume of content available to audiences is growing, the human mind and thus audiences’ ability to enjoy this content remains limited. It is no surprise that audiences experience decision-fatigue and frustration in finding and making time for their favorite content.

The players in the market understand that they are vying for attention in an increasingly saturated economy. To win, they must also help audiences manage their attention.

In a recent podcast on the attention economy, Giancarlo Pitocco highlights the ratcheting up of various tactics (such as auto-play features) between Netflix and YouTube in their fight for consumers’ attention. Netflix and YouTube are just as much technology ventures as they are media ventures. They combine technological advances in recommendation models, curation and best-fit content-to-user algorithms to gain and retain that coveted currency: Audiences’ attention.

The fact of the matter is, each day there is only a limited amount of time available to each consumer to fully engage with an entertainment platform. Audience demand is therefore finite – and SVOD platforms only know this too well. At the heart of the subscriber business model, each company protects the revenue each subscriber represents. And for every moment spent on a platform, each subscriber potentially deprives competitors from a monetization opportunity.

The obvious business implication therefore, is that subscribers, too, are finite.

Demand and subscription: Digital originals are key for SVODs

Media analyst Rich Greenfield argues, “Originals are the No. 1 reason you sign up for an SVOD service,” as reported by Variety. Using global TV demand data, we can offer up concrete evidence that his theory is supported.

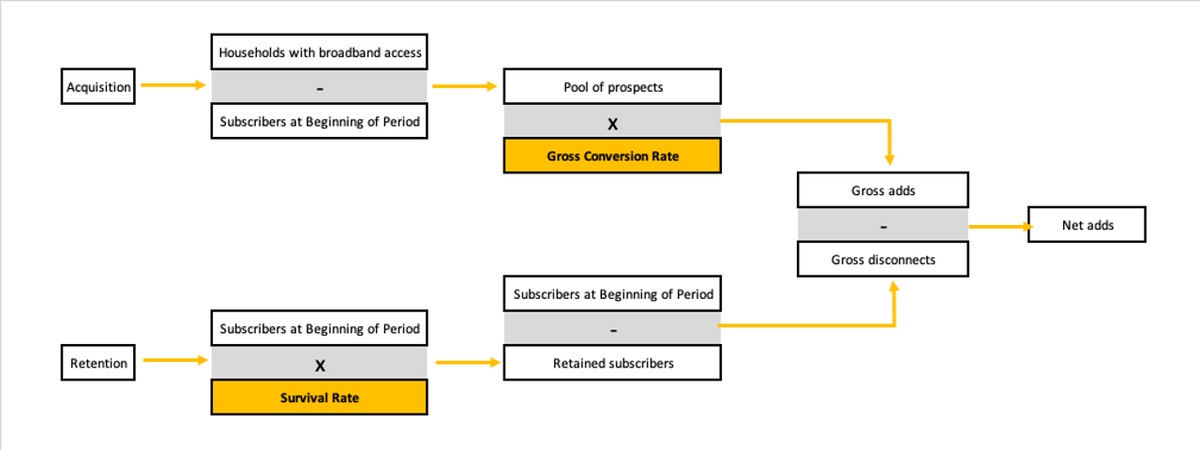

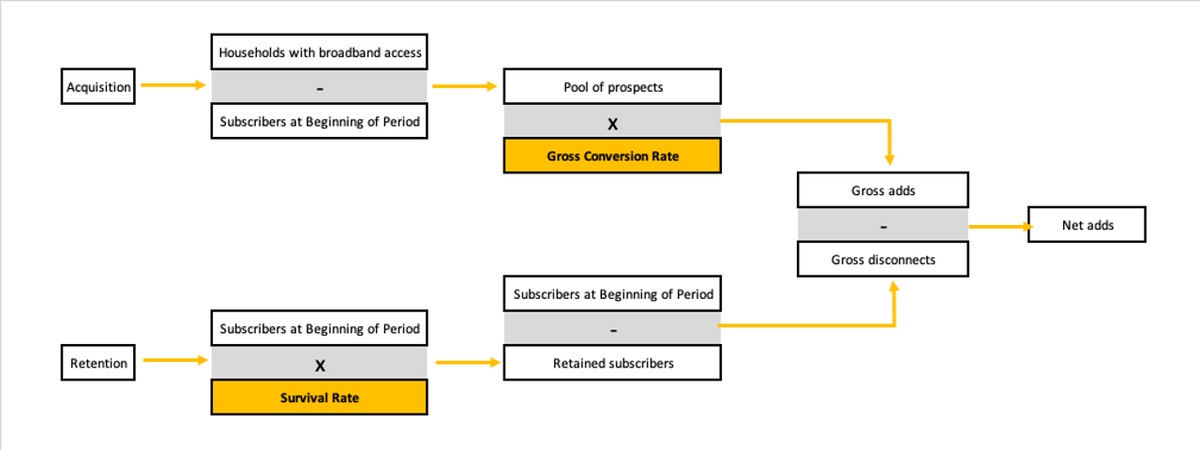

As the chart below demonstrates, Parrot Analytics’ global TV demand analyses reveal that quarterly demand for digital originals and subscription numbers are predictive of one another.

Using a generalized additive model, we found that our model using Demand Expressions (DEx) for digital originals to predict US subscriptions in the millions was statistically significant and robust (i.e., R-squared > 85%). This means that demand, the global currency for the attention economy, explains the majority of the variance in subscription patterns at a macro-level. While the dataset was limited by a lack of daily numbers of Netflix subscribers, it still provides evidence of a strong relationship between the demand for digital originals and subscription.

Not only do our findings underline the relationship between interactive forms of attention and consumer behaviors, but also the value of demand in the attention economy. The finite resource of attention is the prize of the upcoming “Streaming Wars”, a major contributor that drives consumer decision-making, including the services to which they subscribe.

The other finite resource, of course, is the value perception – audiences’ willingness to subscribe and pay for their monthly subscription. Paul Bond reports that a Hollywood Reporter/Morning Consult poll finds that most American households are willing to pay a maximum of $21 in streaming subscriptions per month. Elsewhere, one of our research studies conducted in 2018 revealed that 35% of Americans are willing to pay for more than one streaming service, a percentage likely to rise sharply as cable subscriptions continue to nose dive.

Netflix has a basic plan at a $9, a $13 standard plan, and a $16 premium plan. Disney+ alone will be about $7 monthly, but the Disney-Hulu-ESPN bundle will be $13 per month. HBO Max is expected to cost $15 monthly. Apple TV+ will be released at $5 a month. Meanwhile, Amazon Prime Video’s price is about $13 per month and includes more than access to their streaming content. It’s clear that most users will not be paying for all of these options.

But, can new players expect a significant number of subscribers to sign up in 2020? Does this mean the early streamers (e.g., Amazon, Hulu, and Netflix) may lose subscribers?

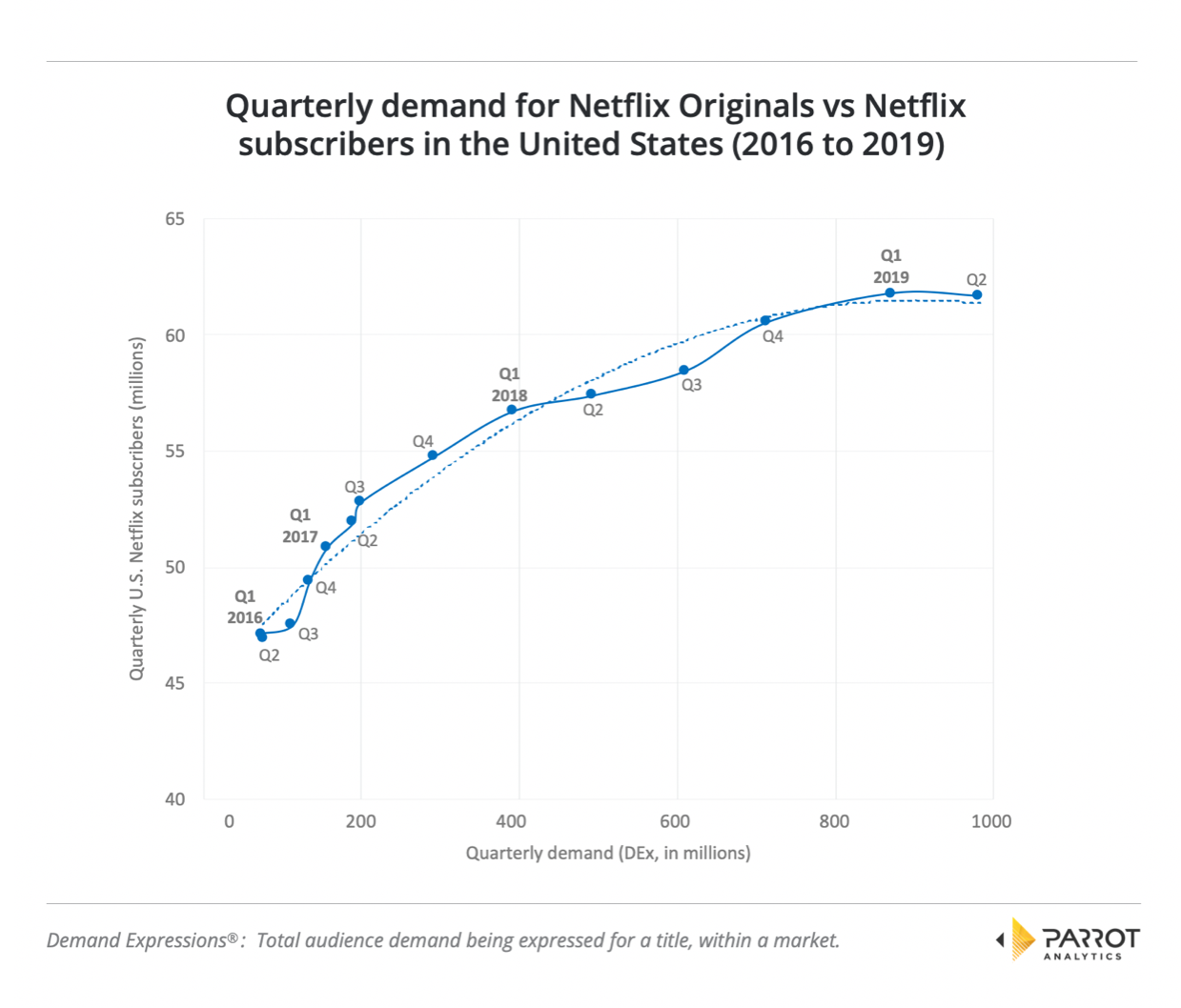

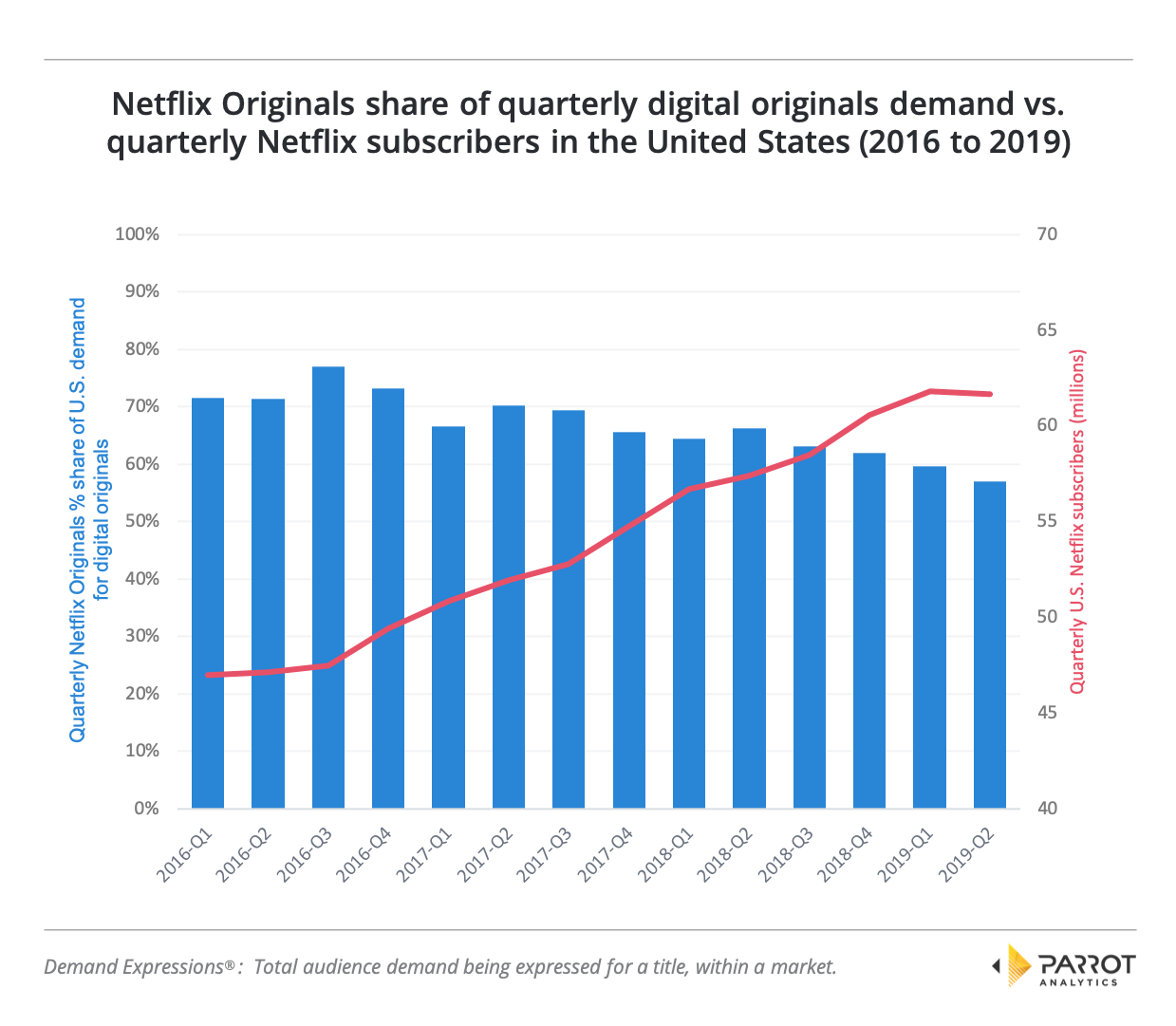

Let us offer up the following chart, which takes another look at Netflix’s US subscribers and compares that to Netflix Originals’ share of digital original demand in the US. We can, therefore, evaluate the demand represented by each subscriber for Netflix and the available opportunity for new streamers.

As seen above, despite Netflix’s increase in US subscribers, these now represent a smaller percent of the total demand for digital originals in the United States. Where the 47 million US subscribers in Q1 of 2016 corresponds with Netflix Originals owning over 70% of the total demand for digital originals in the US, the 61 million domestic subscribers in Q2 of 2019 corresponds with Netflix Originals now making up under 60% of the total demand of all digital originals in the US market.

What can we learn by reflecting on both charts combined in this first article of our series? Netflix’s domestic subscriber rate is slowing down and reaching an asymptote, but the market demand for digital originals is only increasing. Netflix has been slowly losing its share of the US market. The simultaneous decrease of Netflix Originals’ demand share to subscriber ratio represents not only the increased competition but may also point to another challenge: Netflix may be translating less of their new content and subscribers into engaged audiences that are actively immersed in Netflix content.

With the upcoming roll-out of new SVODs soon to tempt audiences and crowd the content ecosystem even further, Netflix will need to fight tooth and nail to maintain its lead. It will need to fight hard to keep consumers from churning and subscribing to some of the new players with competitive pricing (e.g., Apple TV+ at $5 or Disney+ at $7, though these may be worlds apart in terms of the expected content offering). Netflix’s challenge is intensified by its upcoming loss of content; new players such as Disney, NBCU and AT&T plan to take back their coveted content as their contracts with Netflix come to a close.

So, is Netflix in trouble?

And, will these new SVODs be prepared to compete over the long run with the long-standing streaming giant?

You’ll have to see for yourself in Chapter 2: The Crowding Content Ecosystem, which reveals the transformations underway in the digital originals content ecosystem, quantifying and charting the expected threats to Netflix’s dominance.